An interdisciplinary research method for new models for elderly living environments in an aging society

This study focuses on research about the spatial and social living environment of elderly with care demand. It developed from the urge for new ways of thinking about the design of care for elderly in neighborhoods and houses. In a collaboration between an architectural school of education and a social housing association housing the elderly, an interdisciplinary research method to come to new models for elderly living was developed. The study describes the method and main findings. In the Netherlands the demographic transition to an aging society runs parallel with transitions in the policy and practice of elderly care. Due to a steep rise in the cost of care and a shortage of staff, care moves away from institutional buildings and organizations towards a more informal support network with professionals in the background. The research questions addressed in this study concern the everyday life of elderly needing care. Within a one-week stay in a nursing- or elderly care home, participating in the daily life, we aim to get answers through anthropological and par-ticipatory research to understand, document and visualize the needs and living conditions of elderly today. Finally, these data are translated into architectural design. We claim that the person whom we design for should be the first to meet and talk to. In that way we learn about their wishes, needs and capabilities. This argument was our starting point of collaboration. Our methodology leads to unexpected results. The study will show main findings and topics of discussion.

Show LessPeer-reviewed Conference Paper / Full Paper

Integration of needs – inclusive, integrated design enabling health, care and well-being

An interdisciplinary research method for new models for elderly living environments in an aging society

Birgit Jürgenhake*, TU Delft, B.M.Jurgenhake@tudelft.nl; Peter Boerenfijn, Habion, P.Boerenfijn@habion.nl

|

Names of the Topic editors: Journal: The Evolving Scholar DOI: 10.59490/62c3feb8f6f2085d7ed2260f Submitted: 5 Jul 2022 Accepted: 13 Jul 2022 Citation: Jürgenhake, D. & Boerenfijn, P. (2024). An interdisciplinary research method for new models for elderly living environments in an aging society. The Evolving Scholar | ARCH22. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution BY license (CC BY). © 2022 Jürgenhake, D. & Boerenfijn, P. published by TU Delft OPEN on behalf of the authors. |

|---|

Abstract: This study focuses on research about the spatial and social living environment of elderly with care demand. It developed from the urge for new ways of thinking about the design of care for elderly in neighborhoods and houses. In a collaboration between an architectural school of education and a social housing association housing the elderly, an interdisciplinary research method to come to new models for elderly living was developed. The study describes the method and main findings.

In the Netherlands the demographic transition to an aging society runs parallel with transitions in the policy and practice of elderly care. Due to a steep rise in the cost of care and a shortage of staff, care moves away from institutional buildings and organizations towards a more informal support network with professionals in the background. The research questions addressed in this study concern the everyday life of elderly needing care. Within a one-week stay in a nursing- or elderly care home, participating in the daily life, we aim to get answers through anthropological and participatory research to understand, document and visualize the needs and living conditions of elderly today. Finally, these data are translated into architectural design. We claim that the person whom we design for should be the first to meet and talk to. In that way we learn about their wishes, needs and capabilities. This argument was our starting point of collaboration. Our methodology leads to unexpected results. The study will show main findings and topics of discussion.

Keywords: elderly; new models for a home; user centered research;

1. Introduction

This article describes an ongoing study into innovative housing concepts for elderly people in need of care. The main aspect of the research is the development and implementation of a research method to understand the daily routines of the elderly, their needs, more deeply. Then subsequently translate these into architectural models and innovative housing. The method is developed in close collaboration between teachers and students of the Faculty of Architecture at TU Delft and Habion, a Dutch social housing association, housing the elderly. Anthropological research, aimed at observing the daily practices of the residents, their habits and their social networks, is combined with architectural research, aimed at the spatial, material and organizational qualities of the living environment. The resident is central to the research. With this attitude as the starting point, innovative living concepts are gradually developed.

Currently there is a shortage of housing for elderly people and a lack of suitable houses. According to the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport, around 200.000 homes for elderly people must be added by 2030 (Eichholtz, 2021). This also includes the care that many of them will eventually need. If there were 1.4 million people over 75 in the Netherlands in 2020, it will already be 2 million by 2030 (Koerten v. A.). In contrast, the younger age group, between 50 and 74 years old, will decline over the next 10 years, making informal and professional support increasingly difficult. Conversations with the elderly themselves show that the elderly of today want to be able to choose (Witter, Harkes, 2018, p. 8). Many elderly express the wish to continue living at home for as long as possible. For them, this is linked to maintaining independence. A dilemma has arisen. On the one hand, continuing to live independently is a great need, on the other, many homes are not at all suitable for this.

In recent decades, living and care have been separated from each other due to budget cuts by the government. The old retirement home, a result of the welfare state after the Second World War, was abolished as such. Research done in 2013 showed that 800 retirement homes had to be demolished and new construction projects were cancelled (Algemeen Dagblad 21-02-2013). According to Habion, this can also be done differently. “Demolition is not sustainable, it is a destruction of capital and in view of the aging population we could really need those buildings,” says Peter Boerenfijn, director of the housing corporation that has been exclusively involved in the housing of the elderly since its foundation in 1952.

Today, 92% of all over-75s still live at home (Ministerie van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport, 2020). Yet there is a growing number of elderly people who need care and cannot find alternatives due to the disappearance of the retirement home. Between staying at home and the nursing home, there is a gap of suitable houses with care supply. This shortage manifests itself in neighbourhoods where the elderly live in isolation and neglect. In other words, staying at home is not always the best solution, but there are no attractive and suitable alternatives. There is a major challenge in both transformation of the traditional retirement homes and in new construction. This challenge was the starting point for us to start a collaboration between education and practice.

2. Theories and Methods

When writing about seniors or ‘the elderly’, we must state that there is no clear age definition. Our research focusses on elderly people who need care. There are different options for houses, depending on the gradient of care that is provided and not on age. Today elderly people who need more care often end up in a nursing home where the average age is 80+.

In the Netherlands, initiatives have been launched to move care for the elderly from institutional settings, such as nursing homes, to more informally organized care in districts and neighborhoods. As a result, innovative living ideas for seniors are emerging to fill the gap of suitable houses with care supply. In general the care component is the variable component in this living concepts which gets more important and prominent towards the nursing home. Between staying at home and staying in a nursing home, new concepts for living are still developing, but it is not enough yet, and elderly are, like other age groups, a diverse group of people with different demands and wishes. Research into the housing preferences of the elderly shows that one out of six of the average 74 year olds plans to move in the next five years (Koerten, 2020 p. 61-63). Their housing requirements mainly focus on the single-storey house with a small garden in contact with like-minded people.

However, there is still a lot of information missing. It seems that too little attention is paid to how seniors in need of care manage daily life and there is little insight into the use of space by the elderly. How could this knowledge be incorporated into the design and (re)development of the built environment? Anthropological studies show that the domestic practices of the elderly are scarce (Makay, Reinder, 2016).

It is precisely these studies that could provide information about the daily lives of the elderly and provide valuable information about necessary adjustments to the home or the design of new buildings. Knowledge that is still missing and that is obvious. The authors of the seniors organization KBO-PCOB, which conducted the research into the housing needs of the elderly, advise to primarily engage in a dialogue with the target group themselves (Koerten, 2020).

The lack of information about daily practices was the main reason for us to embed this study in a graduation studio of architecture students, which takes two semesters, both 20 weeks (in total 60 ECTS). The first ten weeks are dedicated to research, including a research plan, a fieldwork week, and further elaboration on the research. The second 10 weeks are dedicated to conclusions out of the fieldwork and in-depth research, literature- and case studies. After 20 weeks a translation into design guidelines is done. In the second semester the design site comes into play. The goal of the research is to help students to understand the target group for whom they are designing more profoundly and to build up strong arguments for the design proposal by their research and further literature.

In recent years, anthropological or ethnographic research has increasingly been applied in architecture education. In doing so, the students work from very concrete observations and conversations with the target group to architectural models. This conversations create a much more direct relationship between user and designer.

The main questions addressed in this study concerns the everyday life of elderly needing care: Who is the senior in need of care? What does a day in the life of him/her look like? How are spaces used? What are the meeting moments and where do they take place? The structure of the research method has been refined in the last four years and has now become a purported method for us. We follow four phases:

Phase 1: Understanding anthropological research

Architectural students never have been confronted with anthropological research during their study. Therefore this phase is aimed as preparation for the fieldwork. Learning how to observe requires a neutral view. In her teaching as an anthropologist Andre Gaspar describes how she manages to teach this by using small experimental exercises, and that is what we do as well in the first two weeks (Gaspar, 2018). Students are instructed to spend an hour looking at what they see, without assessment or appreciation. This seems more difficult than expected because our mind immediately interprets and judges. The students continue with this exercise, but now aimed at the elderly. These preparations are appreciated very much by the students, but the outcomes are not taken into account for the further research. Therefore this explanation is kept general here.

Phase 2: Fieldwork

The fieldwork is divided into experimental exercises and on-site explorations.

The first experimental exercise is to spent a day in the city of Delft, sitting in a wheelchair. This opens the eyes how wheelchair users experience the barriers in the building environment. The students found themselves in a constant need to adapt to the built environment and in need to get assistance. Besides this adventure, another exercise is to wear glasses which simulate different kind of eye diseases you might get when you are becoming older. Goal of both exercises is to let the students be aware of those problems when they design for the elderly.

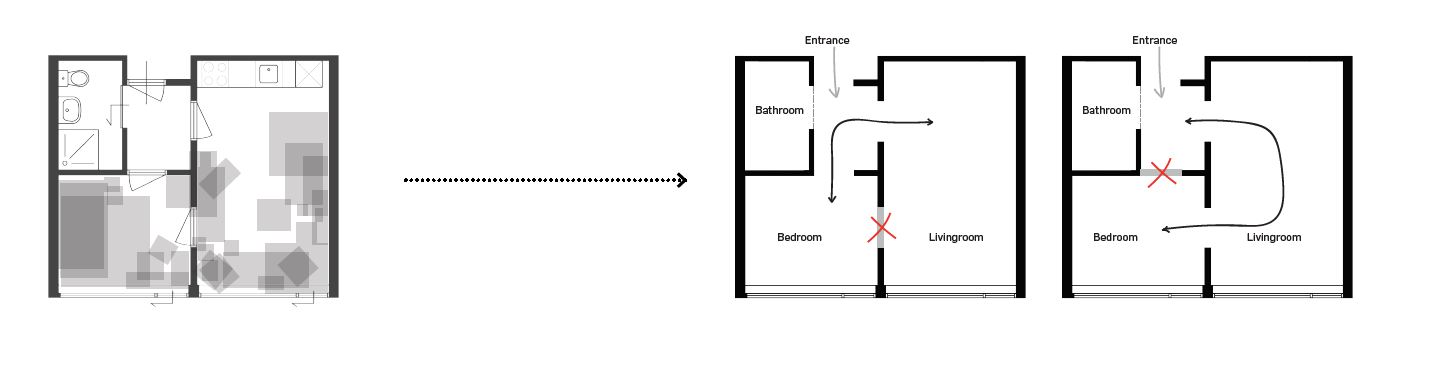

The on-site explorations start after these first experimental exercises. The students stay (in couples) 5 days and nights in one of the selected sheltered elderly homes owned by Habion. They get a guest-room for this stay and they participate as much as possible in the daily activities of the residents. This is a very unique experience for the students. They all start with the same knowledge about observation and interviews, but by going to different nursing homes, each couple uses different ways to get into contact and to generate information. For example students make big posters to let the inhabitants “speak” by post-its asking two questions: ‘what do you like here?’ and ‘What would you like to improve?’ By doing this, they get first-hand information about the place and the wishes of the elderly. The students prepare semi-structured interviews about the daily life of the residents to understand their activities and the places where they take place. The students as well study the lay-out and furniture of the apartments and identify patterns of usage of the apartments (see figure 4), appropriation of space and identity in front of the apartments and in the collective living rooms. They observe the activities in different rooms to see if and how the room changes during the day according to the people who use and adapt it. These observations help the students to understand the daily life of the elderly, the use of the spaces and problems that occur. Later they will be translated to design proposals. The on-site explorations have shown that it is not that easy to speak to every resident. Often the number of respondents is not more than 10-12 persons. Therefore, students develop different strategies to get in touch with the residents: informal conversations, formal semi-structures interviews, attending and organizing activities. The scale of research levels are the direct living environment (500 meter distance), the building and the private room. The care personal and guests are not the focus for the research, the focus lies on the residents. As photography of persons is not allowed, students make lots of sketches or blur the faces on their photographs.

Phase 3: Analysis and in-depth research

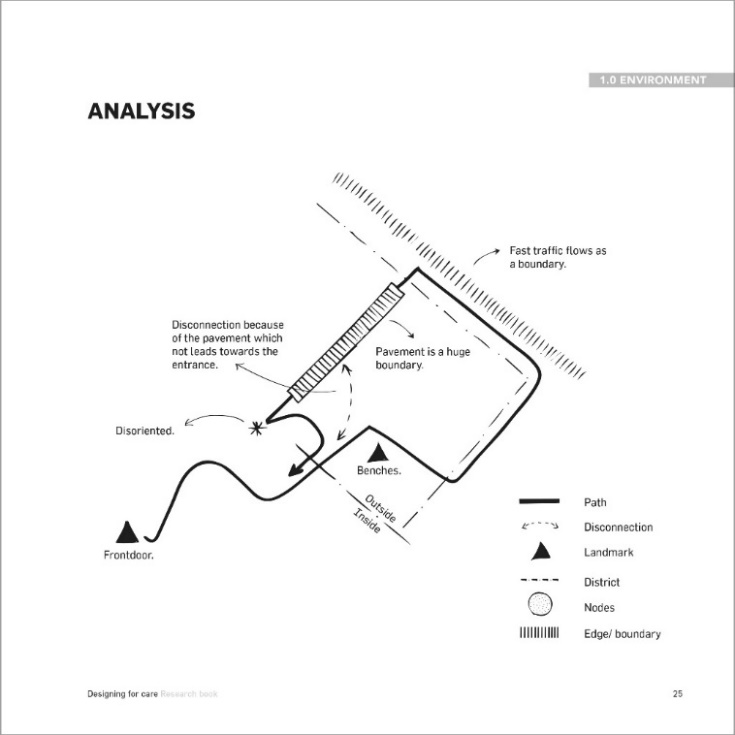

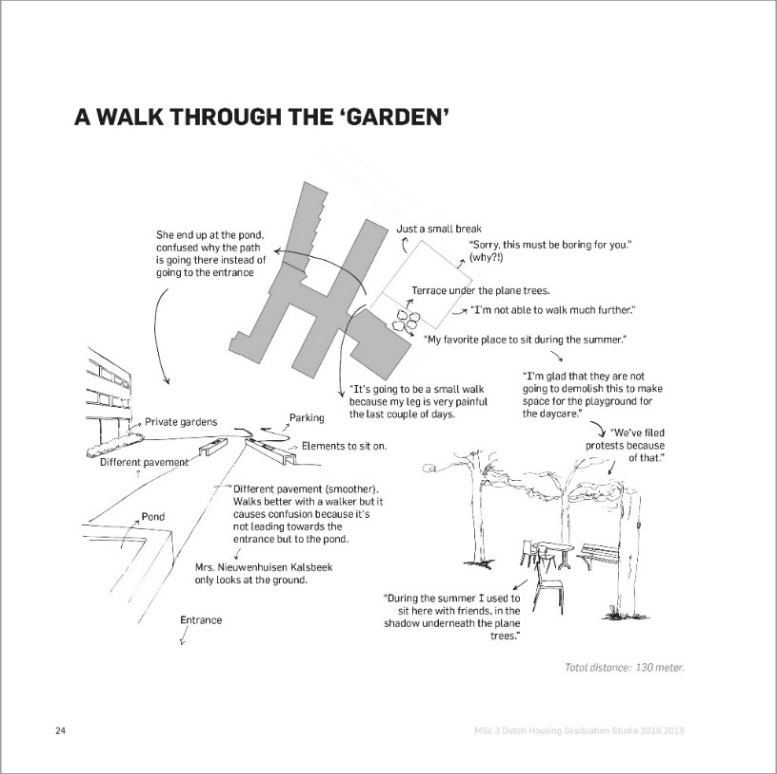

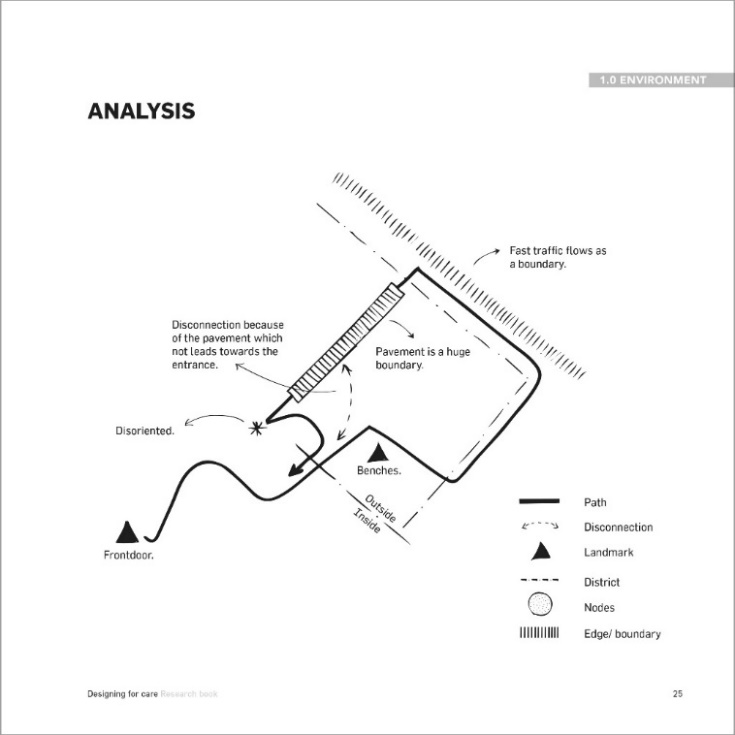

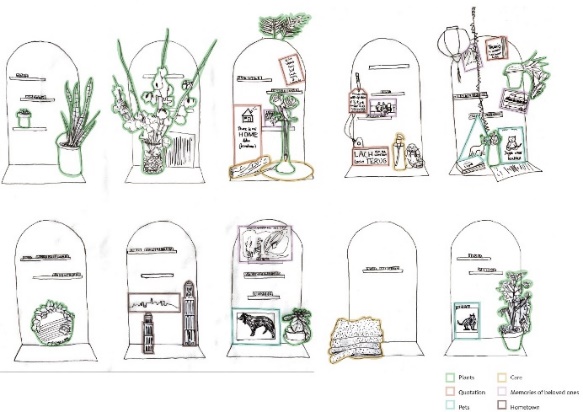

Data from the fieldwork are organized and analyzed by scale and theme per senior home by the students who stay there. The accompanied walks through the neighbourhood are clustered, photo series are organized per topic and place, interviews are compared and the most important statements and quotes of the interviews are summarized. Analytical drawings are made of the accompanied walks to show typical boundaries and disconnections during the walk (figure 3 is one example). Photo series often tell a lot about the usage of spaces, leading to new questions about topics that were touched upon during the visit. For example: students made photo series of all private entrances in one nursing home. All entrances had the same shelf next to the door, meant as a place of identity and recognition for the resident. The series showed that the shelf is used by the care personal to put bottles of hand disinfection there. This makes the shelf less attractive for the residents. This leads to the question of readability of an entrance and simultaneously the needs of space for the care personal.

Thereby the research takes the form of an individual follow-up trajectory. Each student chooses to shed light on one topic (wayfinding, loneliness, identity, lack of meeting places…). This requires further observations, interviews, but also literature study. It often comes to a return day in the senior home. After 10 weeks, the fieldwork is presented per student couple who visited the senior home together as a draft research and the individual follow-up trajectory is presented, but not finished yet. One example of such a follow-up trajectory is shown in table 1. The student interviewed 20 people above 65+ because she wanted to know more about the willingness of sharing spaces among the elderly. Of course this is a small amount of interviewees, but it helped her making decisions for he graduation design proposal.

Phase 4: From data to evaluation and conclusion

The student tries to evaluate the data and reach conclusions through the research that supports his design practice. The evaluation is done in close collaboration with Habion. The translation of information into material and spatial solutions comes into play. The main question now is: what does a conclusion drawn from the fieldwork mean for architecture? In the eight to ten weeks that follow, step-by-step, a translation is made into architectural answers and these are gradually introduced into a concrete design location. The design starts with the scale of the neighbourhood and ends up with a detailed design of the building(s) which is done in the second semester of the graduation.

3. Results

3.1. Results of the fieldwork

At the end of the first semester, there is a fieldwork report of each elderly home the students visited. There is not one general conclusion for all fieldwork that is done. The five topics, as written down below, all students work through, no matter where they stayed:

1. The organization of the building; 2. The residents and their neighbourhood; 3. Usage of spaces in the building; 4. The residents themselves; 5. Residents’ wishes and preferences. In the following we give a summary of the most important findings of this fieldwork as it is our intention to explain the method as such, and not all the outcomes.

1. The organization of the building – The accessibility and the organization of the building and its immediate living environment, the apartments and rooms is studied. Huis Assendorp lies in Zwolle, in the midst of the neighbourhood Assendorp. The ‘Liv-inn’ lies at the edge of the center of Hilversum in a suburban green area.

Figure 1: Two of the sites of the elderly homes visited by students: Left - Huis Assendorp in Zwolle; Right - The Liv-inn in Hilversum (google maps 2022)

Huis Assendorp in Zwolle has a main entrance to the North which is accessible for wheelchairs, a second one is not. Huis Assendorp consists of several wings. A central corridor links them together. Observation showed that there happens to be little social interaction between the residents of one wing and the other. After several conversations it became clear that the reason is a lack of clarity about private versus collective areas and therefore a psychological barrier to enter the other wing.

In the ‘Liv-inn’ in Hilversum, the people of the left wing of the whole complex do not have much contact with those of the right wing, whereas the connection to both wings in the middle part, where a collective area is situated, is good. When the residents visit the collective spaces in the middle, they refuse to sit together with people from the other wing. After having observed this and talked to the residents, the socio-economic difference (rental versus privately owned apartments) seems to be the reason. The people of the left part, which is privately owned, to not come into the area of the right part, the rental houses.

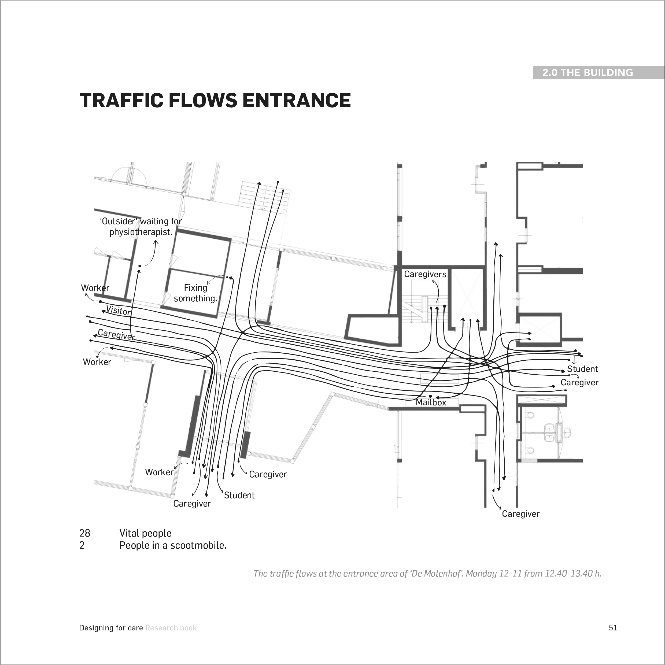

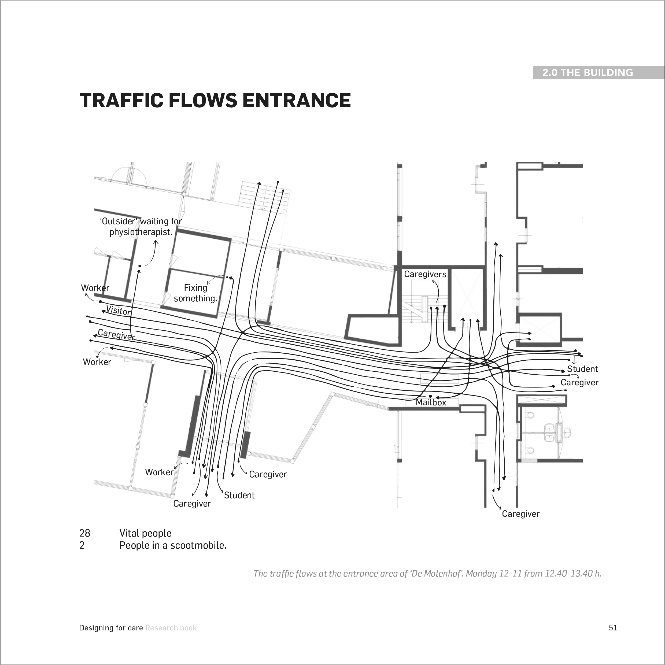

The 'traffic flow' drawing makes clear where 'traffic jams' occur in Huis Assendorp, for example at the entrance or at the elevator (fig.2).

Figure 2. Traffic flows and traffic jam at Huis Assendorp in Zwolle. (Alkema, R., 2019, research book p.51).

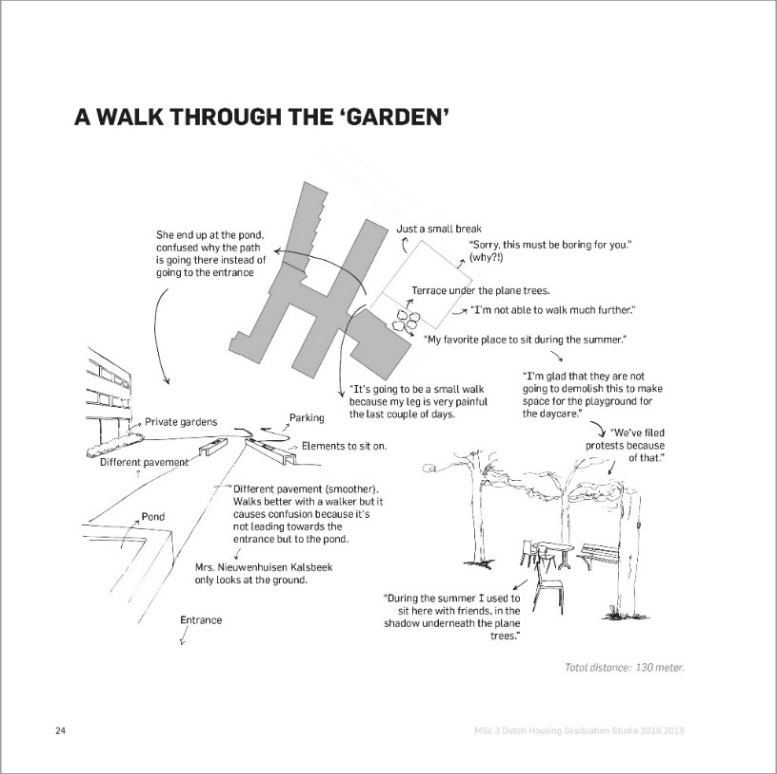

2. The residents and their neighbourhood – the students researched the outside activities in daily life. A walk through the garden or to the supermarket often is the only daily round of an elderly person. “The overall conclusion is that the interruption of their path, the sidewalk, is the biggest problem for the elderly in the city. Most of the time, the sidewalks are interrupted by big, busy streets. These fast traffic flows are overwhelming and elderly people get anxious because of the pace difference between them and the cars. Another problem with the sidewalks around Huis Assendorp is that not all of them are accessible for wheelchairs. They are too small or there are obstacles blocking the path. The traffic lights also form a problem. They turn from green to red too fast for less mobile people, so they end up in a dangerous situation.” (Rosanne Alkema, 2019, research p.31). (Figure 3)

Figure 3. accompanying and observing an elderly person walking with a walker. (Alkema, R. 2019, research book, p.24, 25).

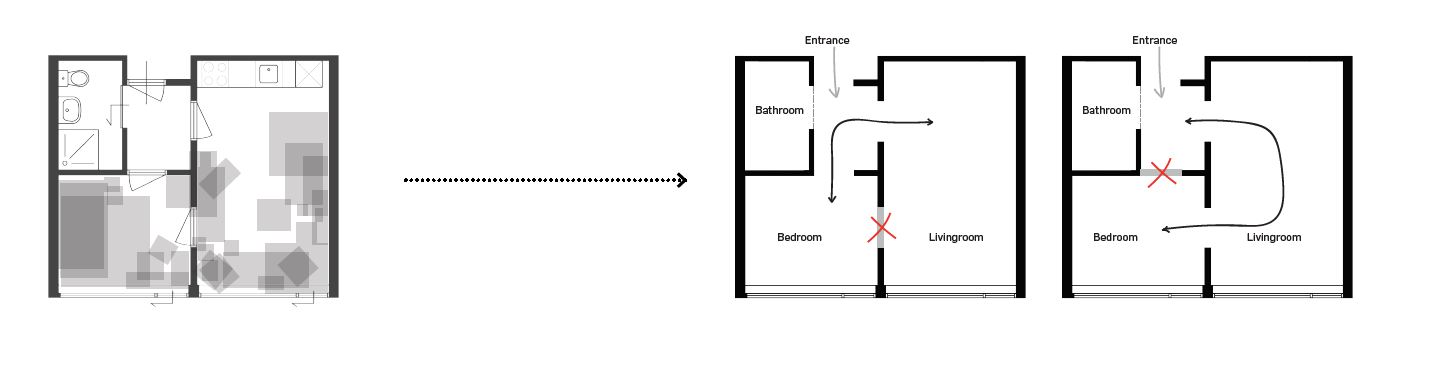

3. Usage of spaces in the building – students especially look at the patterns of use within the different spaces (the collective garden and rooms inside, the circulation spaces, entrance of the apartments and the apartments). By drawing the furniture into the floorplans of the apartments and then putting the floorplans as layers onto each other, they could see certain overlap of places to put furniture and places kept free to walk.

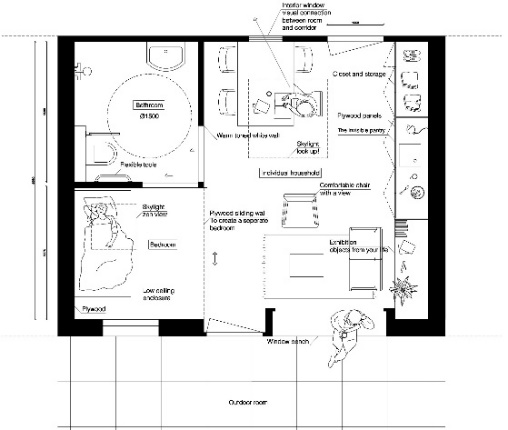

By doing this, students realized that the door from the living room to the bedroom often is blocked by furniture. The inhabitants frequently told the students that they do not want to see the bed during the day because they think that the bed is the place to die. Next to this, the furniture of the bedroom blocked the window (figure 4).

Figure 4. In grey the places of the furniture of several apartments put as layers on to each other in Huis Assendorp in Zwolle. The right floorplan shows the blocked door. (Alkema, R., 2019, research book p.89,99).

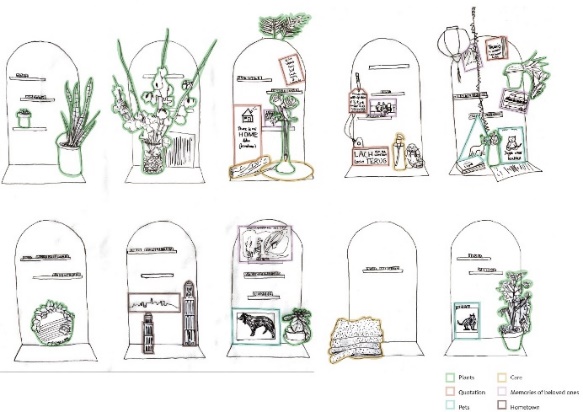

The entrance doors of the apartments seem to be important to personalize. This makes recognition much easier.

Figure 5. Personalization at the entrances in Loenen (Borgdorff, S., 2021, research book, p.48-51)

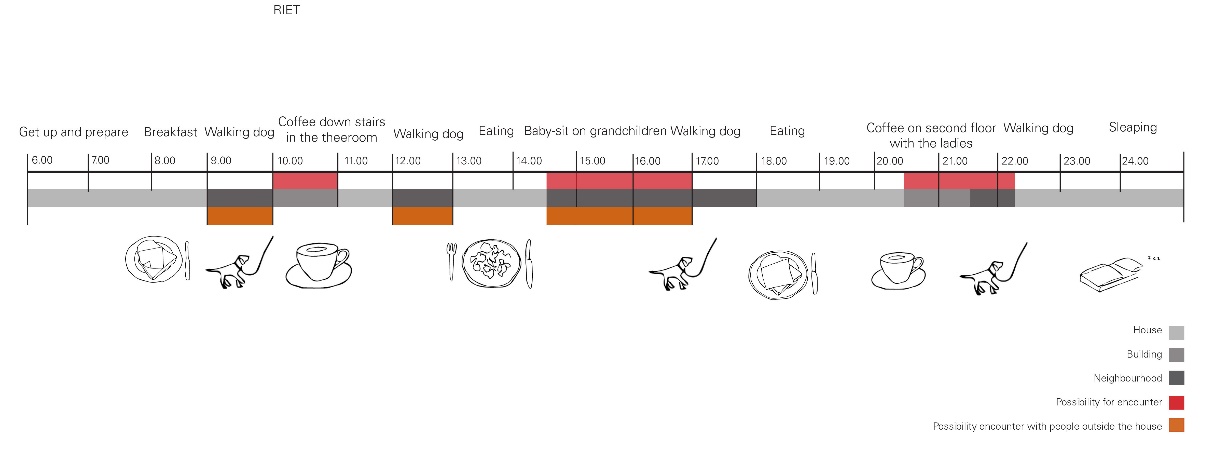

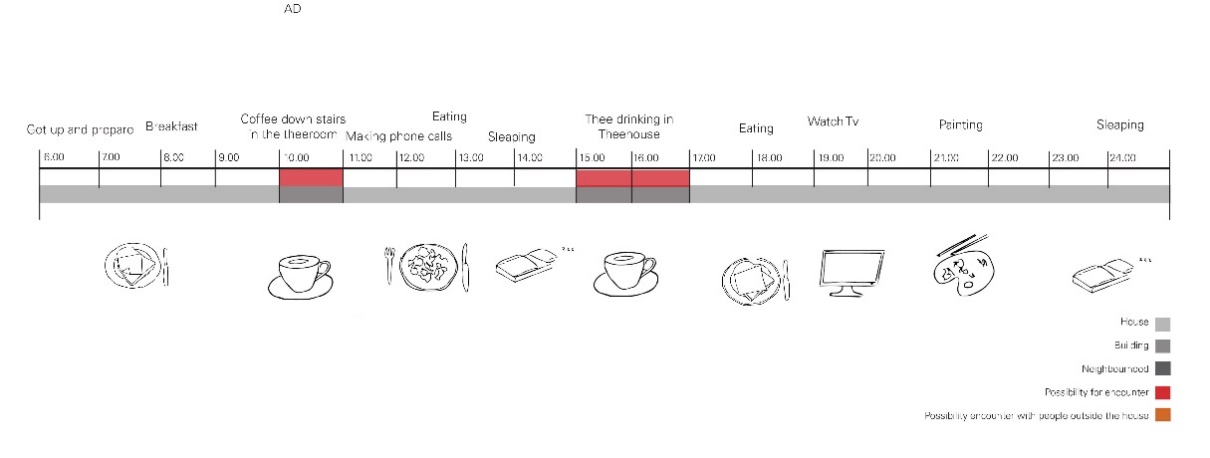

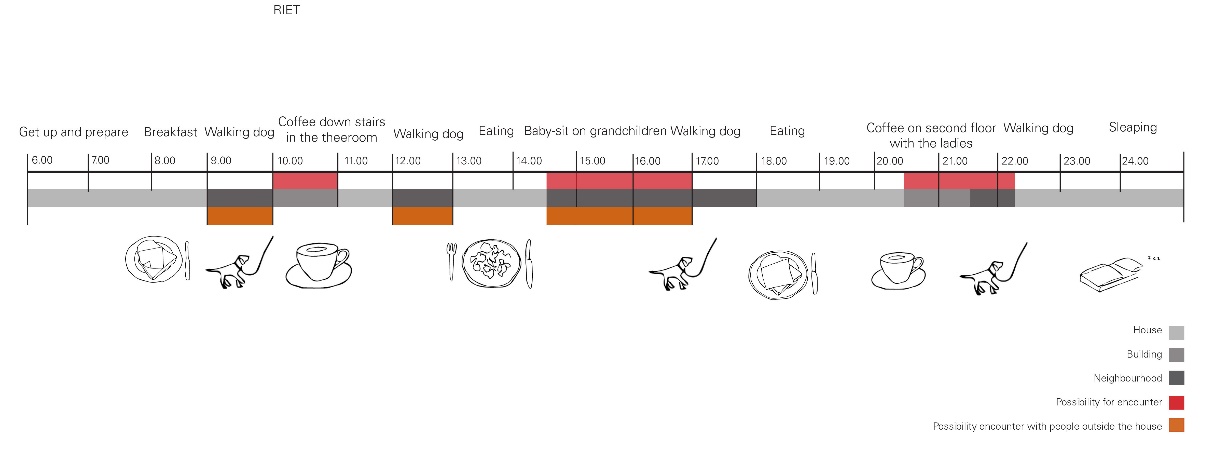

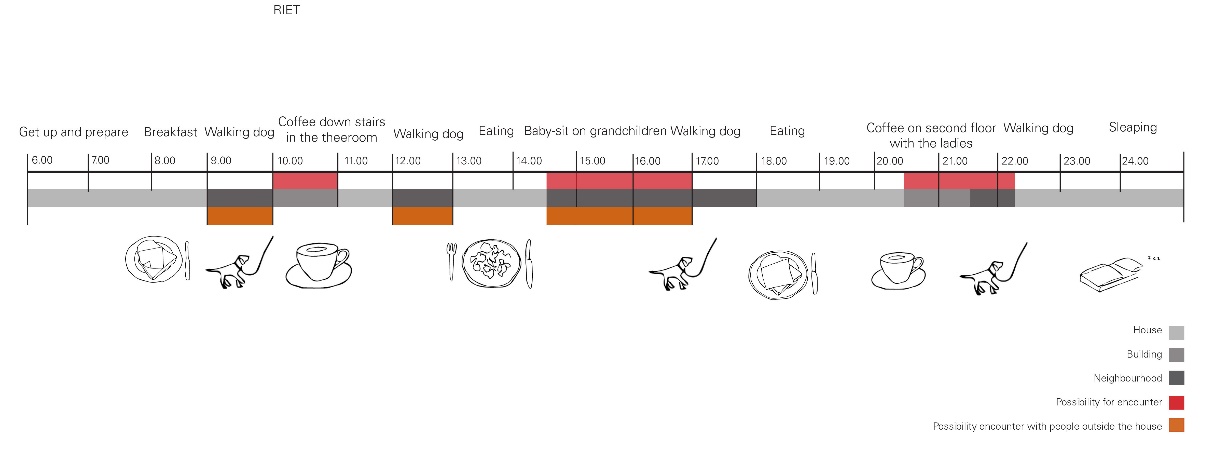

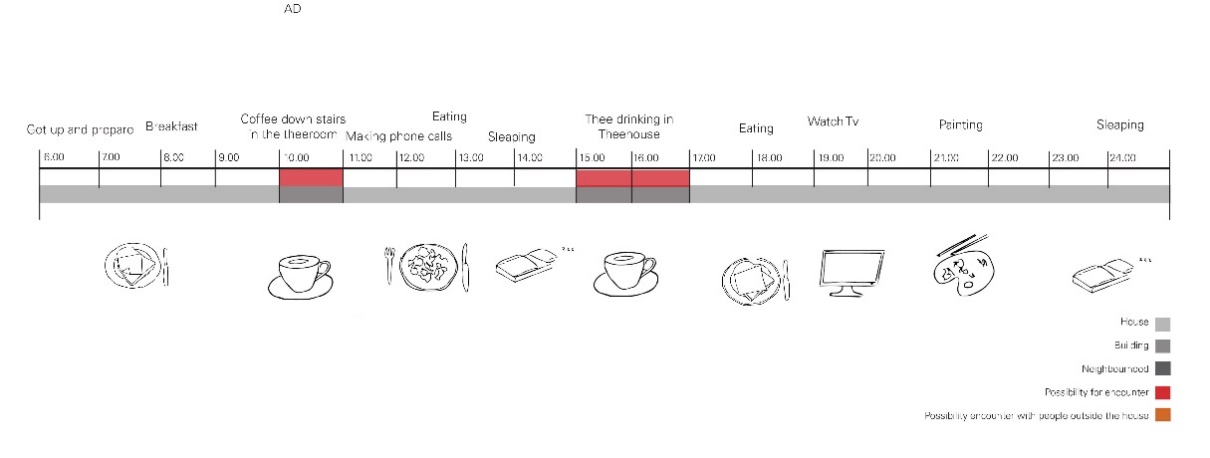

4. The residents themselves are as different as could be. What do they have in common? Meanwhile, a talk during the daily round gives information about their daily activities. In analysis drawings, students compare the residents’ activities and moments of encounter. Riet for example (Fig. 6) walks four times a day with her dog. The moments of encountering neighbours are frequent, inside and outside the building. Ad meets others at the moments for coffee, but asks for a taxi twice a week to meet friends outside. The different schematics of the elderly show their activity level.

Fig. 6 – Riet (above) and Ad (below) and their pattern of daily life (Kieft, E., 2020, research book, p.20,21). As Riet walks her dog, she comes outside every day. Ad has a different daily life.

Fig. 6 – Riet (above) and Ad (below) and their pattern of daily life (Kieft, E., 2020, research book, p.20,21). As Riet walks her dog, she comes outside every day. Ad has a different daily life.

It must be clear that this work is very much individual. The relation between a student and the elderly may foster very different dialogues. Nevertheless, certain aspects pop up regularly. They are therefore often themes for further research.

- From passive behaviour to self-reliance

- From dependence to independence

- Loneliness

- Social meetings

- Meaning of life

- Distance between residents and the neighborhood

- Feeling that you do not belong anymore

- Homesickness

- Dementia – able to stay where you are?

- Reciprocity between the elderly and other age groups

- Willingness of sharing rooms with others

- Resilient housing to stay at home as long as possible

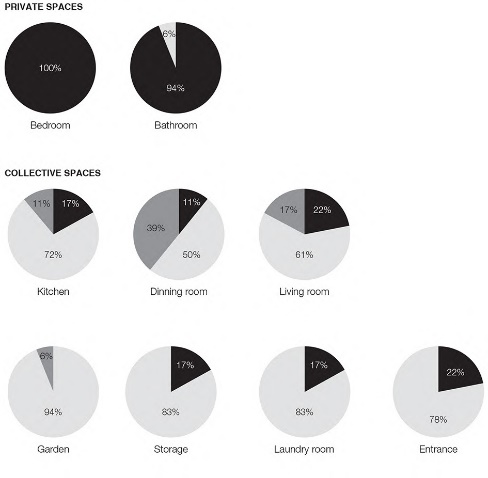

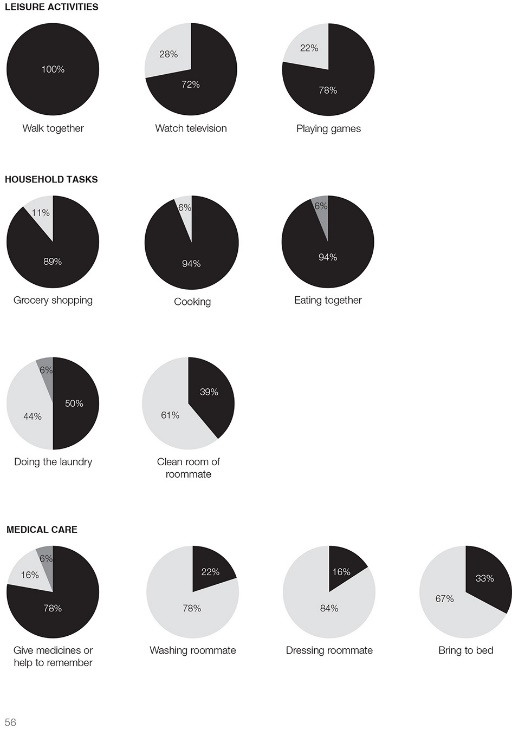

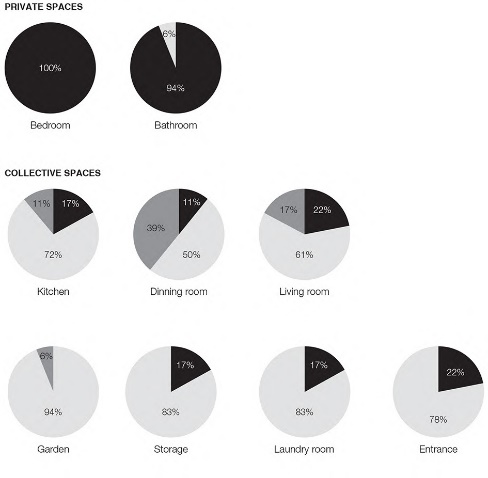

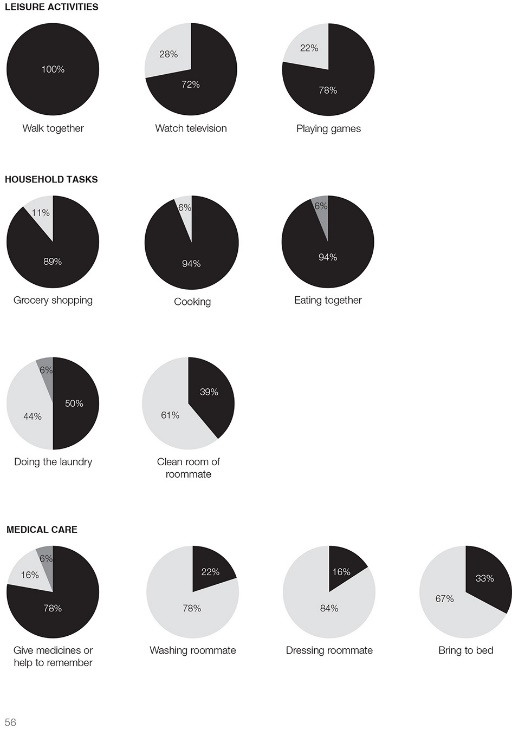

5. Residents’ wishes and preferences – Student Marijn Bouwman decided to do a follow-up research, which she did not do in the elderly home, but with older people in her own living environment. She made little room models and used them to discuss the willingness of sharing the room and helping others in their own living environment. Her results show that people do not want to share the bedroom, neither the bathroom. Only half of them would share the dining room and a bit more the living room. Functional rooms and gardens are no problem to share. Most people are willing to help with a household task, or walk together, but more private actions like dressing are problematic (table 1).

Tabel 1.b: The willingness to help with certain activities. Black = willing to help, Light grey = not willing to help, middle grey = perhaps (Bouwman, M., 2019, research book, p.54, 56)

3.2.First translations into architectural results

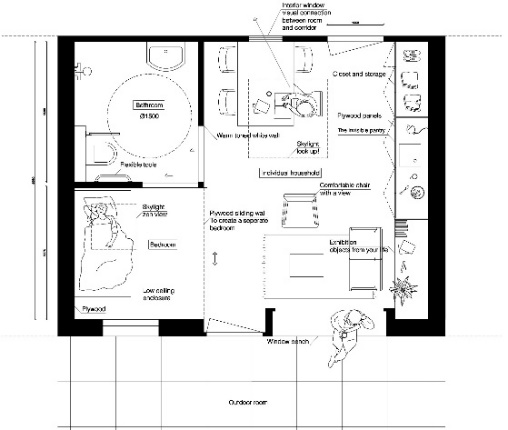

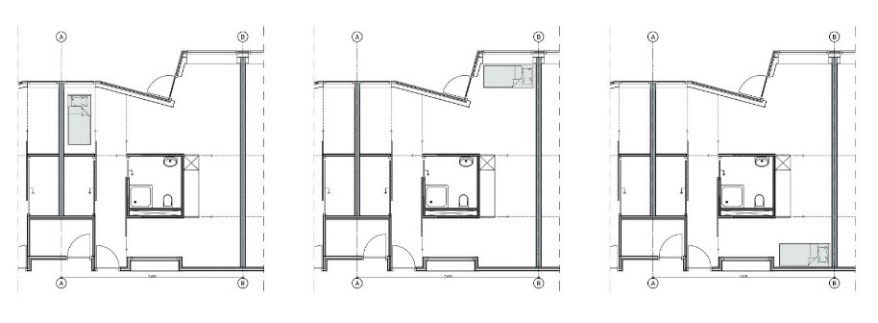

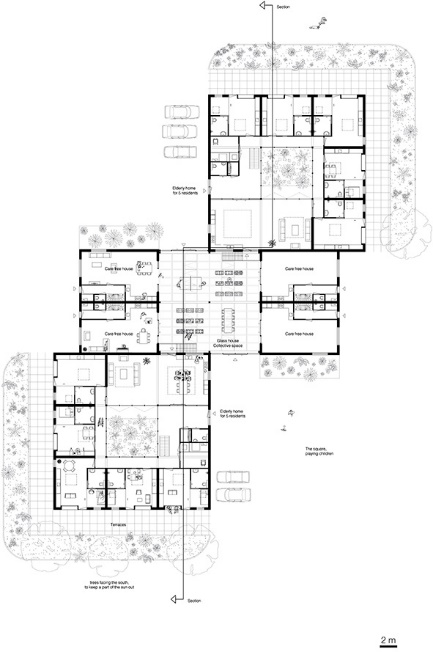

The design sites are in the Netherlands and chosen because of the future plans for senior homes. The daily walks (Fig. 3) inspired S. Alkema to design an ensemble of buildings that form one big courtyard, open towards the neighbourhood. Walking routes through and around the building give the residents several options for a safe daily walk. There is an extravert and an introvert walking route through the building ensemble with stimuli and places, inside and outside, to rest and to meet others. As almost all students heard from the seniors, it is not normal to live exclusively with 80+, to the south of this ensemble, a children day-care is placed, together with family houses. Due to the observations during her fieldwork, the student realized that the residents do not want to see the bed during the day, but once they get sick, it’s nice to give the bed a good place. Therefore, she designed an apartment in which the bed can move to three different places, depending on the situation.

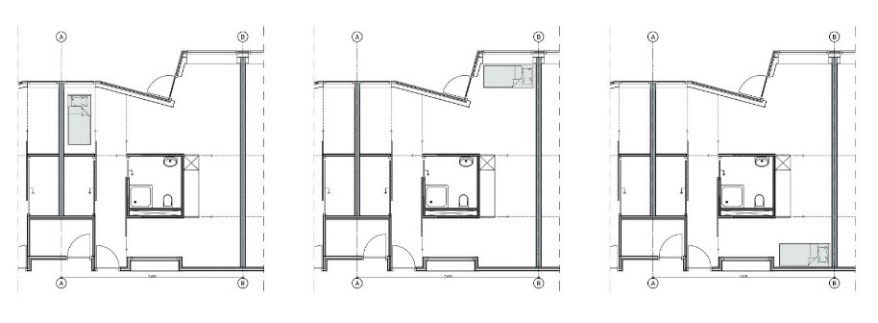

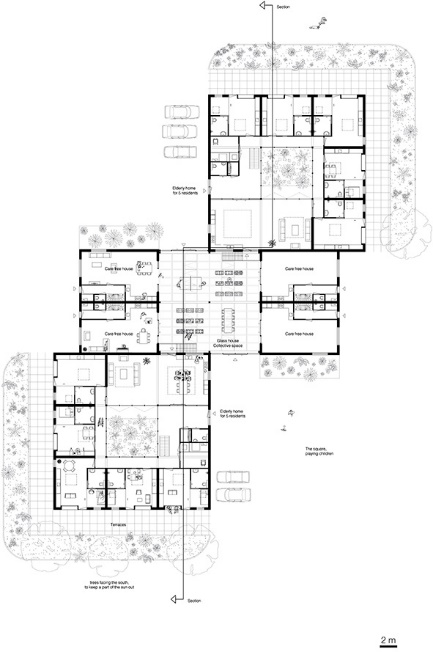

Figure 07. On the left you see the ensemble of four buildings and the walking paths outside, on the right, three positions for the bed with sliding doors to close the place or the room. (Alkema, R., 2019, book of drawings, p.1 and presentation slide 59).

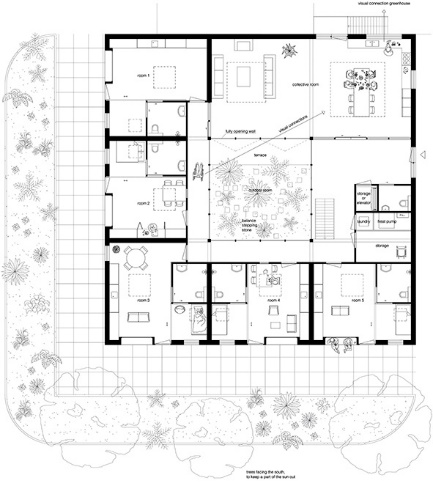

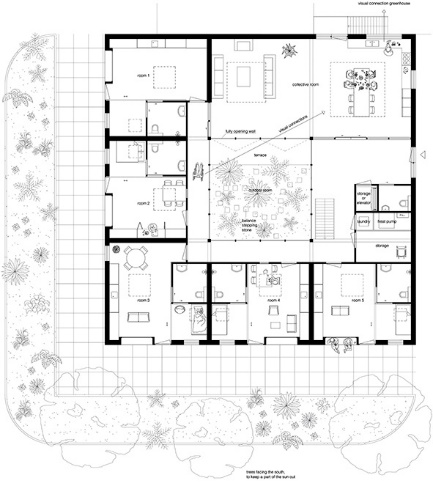

The interviews Marijn Bouwman conducted in het follow-up research phase about the willingness to share rooms and to help each other showed that there are certain private actions like washing somebody which need to be done by professionals, whereas cooking for somebody and eating together, most people are willing to do so. This information resulted in dwelling clusters with collective living for the elderly and family living in-between. Because of the need of professional care, six co-living areas with in total 30 seniors would get one care-office as well. Her fieldwork showed that not everybody likes to sit in the collective kitchen with the others. Therefore each apartment has a little pantry as well and a good view towards the common room to see, who is sitting there.

Figure 8. On the left you see one cluster of collective living apartments for the elderly and family living in-between; on the right, one collective living apartment group for five elderly on the ground floor and one group on the first floor. (Marijn Bouwman, 2019, design book, p.15,19)

Figure 9. One elderly’s apartment and the cluster of co-living. During the day the bed will be hidden behind a sliding door. Each apartment has its own pantry and enough closets. There is a bench combined with the window to sit in front of the house. The cluster of co-living (one story high or two stories) and family houses are combined with a winter garden. (Marijn Bouman, 2019, design booklet, p.13,27)

4. Discussion

In the near future one out of four inhabitants will be over 65 years old. These elderly will be better educated, healthier and richer than the present. The existing housing stock is based on past experiences and mainly designed for families. Furthermore, there will be a shortage of professional staff and informal support. This makes it necessary that elderly support each other and stay as self-reliant as possible. To anticipate on this transition of society more research and in other scientific fields like anthropology, mobility and preventive health needs to be done by architects and urban planners to understand the needs of the elderly today and our near future because traditional designing will not provide the solutions.

5. Conclusions

We have never experienced an aging society before. New research methods, such as combining anthropological and architectural research, provide insight in the daily life of the elderly. Lots of elderly, but as well younger people provided us with information. After four years of work with the master students we can conclude that the method brought us new insides into the daily life of the elderly who need care as well as insides in the willingness and limits of others to help. We saw lots of translations to design proposals, not all of them could be shown in the limited context of this text.

By using this method, the students designed innovative living concepts in which the elderly could get old by their own standards, as independently and self-reliantly as possible. The cooperation between TU Delft and Habion not only gives the students the opportunity to observe the daily life of elderly people but also provides a living lab to test innovative ideas.

References

-

Ahli, S. (2019). Hoe het oude verzorgingshuis een nieuw leven krijgt. Hoe het oude verzorgingshuis een nieuw leven krijgt - Skipr

-

Algemeen Dagblad (21-02-13). Sluiting-800-verzorgingshuizen-dreigt. www.ad.nl/gezond/sluiting-800-verzorgingshuizen-dreigt~aad43e0e/ (consulted 17-11-2021)

-

Alkema, S. (2019). Master thesis The Elderly Movement: Elderly in charge of their own flows in life again. TU Delft: http://resolver.tudelft.nl/uuid:74561db2-3a25-4773-81a4-fbc86d2a284f

-

Altman, I. (1975). The environment and social behaviour. Privacy, personal space, territoriality and crowding. Monterey: Brooks/Cole.

-

Amerlinck, M.-J. (2001). Architectural Anthropology. Westport, CT: Praeger.

-

Atelier Bow Wow (2013). Graphic anatomy. Tokyo: Toto.

-

Borgdorff, S. (2020). Master thesis AGE - designing for active generations of elderly. TU Delft: http://resolver.tudelft.nl/uuid:d15ab869-2e9b-4758-882e-2d26b414ed9c

-

Bouwman, M. (2019). Master thesis Fun by grey. TU Delft: http://resolver.tudelft.nl/uuid:8b7e5027-eea4-478e-9030-fcb6c649fa65

-

Buti, L.B. (2018). Ask the right question. A rational approach to design for All in Italy. Springer Switzerland.

-

Castelijns, E., Kollenburg, A. van (2013). De vergrijzing voorbij. Uitgever Berenschot. Utrecht, The Netherlands.

-

Collier, J.(1986). Visual Anthropology. Photography as a Research Method. University of New Mexico Press.

-

Cumming, E., Henry, W.E. (1961). Growing old. The process of disengagement. New York: Basic Books.

-

Dannefer, D. (1989). Human action and its place in theories of aging. Journal of aging studies, Volume 3 Issue 1 , p. 1-20.

-

Davey, J., Nana G., de Joux, V., Arcus, M. (2004). Accommodation options for older people in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Wellington, New Zealand, NZ Institute for Research on Ageing/Business & Economic Research Ltd, for Centre for Housing Research Aotearoa/New Zealand

-

Eichholtz, P. (2021). Woningtekort is ook een probleem voor de zorg - Zorg&Sociaalweb

-

Eyck, A. van (1959). Het verhaal van een andere gedachte. Forum 1959, nr. 7.

-

Eyck, A. van (1959) Drempel en ontmoeting: de gestalte van het tussen. Forum 1959, nr.8

-

Gaspar, A. (2018) Teaching Anthropology speculatively. https://doi.org/10.4000/cadernosaa.1687

-

Gehl, J. (1978) Leven tussen huizen. Zutphen: De Walburg Pers.

-

Hertzberger, H. (1982) Het openbare rijk. Delft: Delft University Press.

-

Hertzberger, H. (1984) Ruimte maken, ruimte laten. Delft: Delft University Press.

-

Ingold, T. (2016) Lines: A Brief History. London: Routledge.

-

Katz, S. (2000). Busy bodies: activity, aging and the management of everyday life. Journal of aging studies, Volume 14 issue 2, p.135-152.

-

Kieft, E. (2020). Master thesis Reducing distance to create a sense of belonging and get familiar with one another. http://resolver.tudelft.nl/uuid:57f109a2-41c4-424a-8c78-b9a089385311

-

Koerten v. A. (2020). Onderzoek woonwensen van senioren: Hoe willen senioren wonen? Geron, Tijdschrift over ouder worden & samenleving. Volume 22 issue 1, p. 61-63. www.gerontijdschrift.nl

-

Kontos, P.C. (1998). Resisting institutionalization: constructing old age and negotiating home. Journal of ageing studies, Volume 12,issue 2, p.167-184.

-

Lucas, R. (2020). Anthropology for Architects: Social Relations and the Built Environment. London; New York: Bloomsbury Visual Arts

-

Makay, I., Reinder, L. (2016). Het mankeerde (t)huis – een visuele antropologie over de woonpraktijken van ouderen in Brussel. Garant, Antwerpen, Apeldoorn.

-

Ministerie van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport. (2020) monitor-langer-thuis. www.rivm.nl/monitor-langer-thuis/resultaten/resultaten-actielijn-3-wonen/percentage-75-plussers-dat-aangeeft-dat-hun-huidige-woning-geschikt-is

-

Pink, S. (2006). The future of visual anthropology. Engaging the senses. Londen en New York: Routledge.

-

Pink, S. (2006). The future of visual anthropology. Engaging the senses. Londen en New York: Routledge.

-

Powell, K. (2010). Viewing Places: Students as Visual Ethnographers. Art Education, 63(6), 44–53

-

Rapoport, A. (1969). House Form and Culture. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

-

Reed, J., Payton, V.R. , Bond, S. (1998). The importance of place for older people moving into care homes. Social science & medicine, Volume 46 issue 7, p. 859-867

-

Roesler, S. (2014). Visualization, embodiment, transfer: Remarks on ethnographic representations in architecture, Candide. Journal for Architectural Knowledge, (8), pp. 10–27.

-

Rose, G. (2016). Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to Researching with Visual Materials. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE.

-

Rothuizen, J. (2015). The Soft Atlas of Amsterdam: Hand Drawn Perspectives from Daily Life. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

-

Stanczak (2007). Visual Research method. SAGE Publications.

-

Stender, M. (2017). Towards an Architectural Anthropology—What Architects can Learn from Anthropology and vice versa. Architectural Theory Review, 21(1), pp. 27–43.

-

Vincent, J. (2003). Old age. Londen en New York, Routledge.

-

Ware, C. (2012). Building Stories. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Pantheon. Whyte, W. H. (1980) The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces. New York: Project for Public Spaces.

-

Witter, Y., Harkes, D. (2018). Bouwstenen voor de toekomst, 15 jaar werken aan samenhang in wonen, welzijn en zorg. Aquire publishing Zwolle.

-

Whyte, W. H. (1980). The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces. New York: Project for Public Spaces.

Zorgvoorbeter.nl

Figures (17)

More details

- License: CC BY

- Review type: Open Review

- Publication type: Conference Paper

- Submission date: 5 July 2022

- Publication date: 22 March 2024

Citation

Jürgenhake, D. & Boerenfijn, P. (2024). An interdisciplinary research method for new models for elderly living environments in an aging society [preprint]. The Evolving Scholar | ARCH22. https://doi.org/10.59490/62c3feb8f6f2085d7ed2260f

No reviews to show. Please remember to LOG IN as some reviews may be only visible to specific users.